Halloween Pranks

Various places around young Sioux Falls

All Hallow’s Eve, Hallow Eve, Hallowe’en, or Halloween, as we now call it, has been celebrated throughout Sioux Falls’ history. Parties were held all over town, both public and private, and excitement prevailed.

In the Halloween 1887 edition, the Argus Leader read: “Halloween tonight. The tub and apple, the ball of yarn, and the midnight incantations in front of the looking glass will be once more the foolish occupation of the giddy youth.” In its coverage of a party at All Saints School, it was reported that the girls were able to stay up as late as they wanted and “convivial hilarity held joyful sway.” Almost as a counterpoint to these parties, bands of miscreants flooded the city in chaos, causing no small amount of trouble.

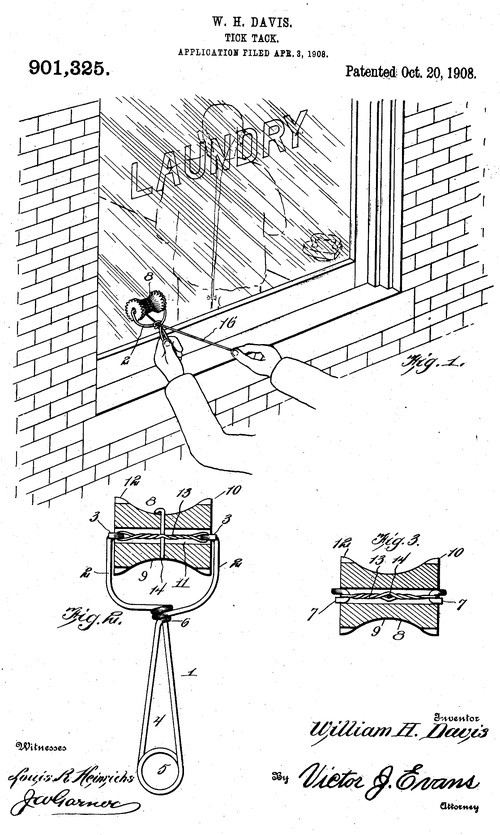

As early as 1887, harmless pranks and jokes gave way to destruction of property throughout the normally quiet streets of the city. To begin with, the pranks and jokes took the form of noisemakers. An improvised device, known as a tick-tack, could be made with a wooden spool with serrations carved in the edges. This spool would be placed on a spindle and wound with string. The contraption would then be set against the window of the intended victim. When the string was pulled, it would produce a rattling cacophony that was especially shocking on an otherwise quiet night.

As early as 1887, harmless pranks and jokes gave way to destruction of property throughout the normally quiet streets of the city. To begin with, the pranks and jokes took the form of noisemakers. An improvised device, known as a tick-tack, could be made with a wooden spool with serrations carved in the edges. This spool would be placed on a spindle and wound with string. The contraption would then be set against the window of the intended victim. When the string was pulled, it would produce a rattling cacophony that was especially shocking on an otherwise quiet night.

William H. Davis patented a particular design of Tic-tac in 1908. Not sure if the manufacture of these ever took off, or if he just used the patent to sue pranksters who used it on him.

Horse fiddles were another noisemaker used. They were wooden blocks with handles that would produce a ratcheting sound when swung around.

Ding dong ditch was also employed on houses with doorbells, though the practice did not carry this catchy moniker. While these pranks were seen as harmless frivolity, destruction of property began to creep into the repertoire of some.

In 1898, a few pieces of sidewalk were overturned, as were some horse steps - small stairs used to mount horses. At the time, sidewalks were made from wooden planks, so in most cases, they could just be put back in place until they were upset again the following year. By 1900, the celebration was escalating; outhouses began to be tipped over, and unsecured items would often be found in the next yard, if at all.

In 1899, more sidewalks were thrown over, along with more outhouses, and J. M. Robbins had to search for three hours before finding his lumber wagon, which had been take from his barn. An old omnibus — think horse-drawn bus — was taken from A. H. Peck and left in two pieces - partly on his sidewalk, partly in his yard. Some miscreants even painted on downtown windows and doors.

Starting in 1900, the wooden sidewalks were being replaced by cement panels, which were much more difficult to turn over. While the sidewalk pranks were mostly phased out, other troublesome pranks continued. The police were not asleep for any of this nonsense. Every year a dire warning would be issued and a full compliment of officers, sometimes mounted, would be on duty the evening of Halloween to make sure things didn’t get too out of control.

The Halloween antics went a bit too far in 1911: Some ne’er-do-wells caused trouble on the streetcar lines, which might have ended a life were it not for the quick reactions of one motorman. Near Morrell’s, at the junction where the east side line approached the packinghouse spur, the tracks were slicked with soap. To make matters worse, the switch was flipped, which caused the packinghouse trolley to turn onto the eastbound line. The switch had also been covered, so the motorman on the packinghouse line was unaware of the situation. There was a trolley waiting on the eastbound line, and its motorman noticed the packinghouse trolley turning onto his line and immediately put his car in reverse. The packinghouse trolley was unable to stop on the slick lines, but the eastbound car, creeping to pick up speed, was able to reduce the impact of the collision. The streetcar was damaged and the east line had to be shut down for the night. Passengers were shaken, but well enough to walk home.

After the streetcar incident, reports of destruction on Halloween became scarce. Perhaps the delinquents were more willing to offer a choice to their potential victims after that. Trick or treat?

Ding dong ditch was also employed on houses with doorbells, though the practice did not carry this catchy moniker. While these pranks were seen as harmless frivolity, destruction of property began to creep into the repertoire of some.

In 1898, a few pieces of sidewalk were overturned, as were some horse steps - small stairs used to mount horses. At the time, sidewalks were made from wooden planks, so in most cases, they could just be put back in place until they were upset again the following year. By 1900, the celebration was escalating; outhouses began to be tipped over, and unsecured items would often be found in the next yard, if at all.

In 1899, more sidewalks were thrown over, along with more outhouses, and J. M. Robbins had to search for three hours before finding his lumber wagon, which had been take from his barn. An old omnibus — think horse-drawn bus — was taken from A. H. Peck and left in two pieces - partly on his sidewalk, partly in his yard. Some miscreants even painted on downtown windows and doors.

Starting in 1900, the wooden sidewalks were being replaced by cement panels, which were much more difficult to turn over. While the sidewalk pranks were mostly phased out, other troublesome pranks continued. The police were not asleep for any of this nonsense. Every year a dire warning would be issued and a full compliment of officers, sometimes mounted, would be on duty the evening of Halloween to make sure things didn’t get too out of control.

The Halloween antics went a bit too far in 1911: Some ne’er-do-wells caused trouble on the streetcar lines, which might have ended a life were it not for the quick reactions of one motorman. Near Morrell’s, at the junction where the east side line approached the packinghouse spur, the tracks were slicked with soap. To make matters worse, the switch was flipped, which caused the packinghouse trolley to turn onto the eastbound line. The switch had also been covered, so the motorman on the packinghouse line was unaware of the situation. There was a trolley waiting on the eastbound line, and its motorman noticed the packinghouse trolley turning onto his line and immediately put his car in reverse. The packinghouse trolley was unable to stop on the slick lines, but the eastbound car, creeping to pick up speed, was able to reduce the impact of the collision. The streetcar was damaged and the east line had to be shut down for the night. Passengers were shaken, but well enough to walk home.

After the streetcar incident, reports of destruction on Halloween became scarce. Perhaps the delinquents were more willing to offer a choice to their potential victims after that. Trick or treat?